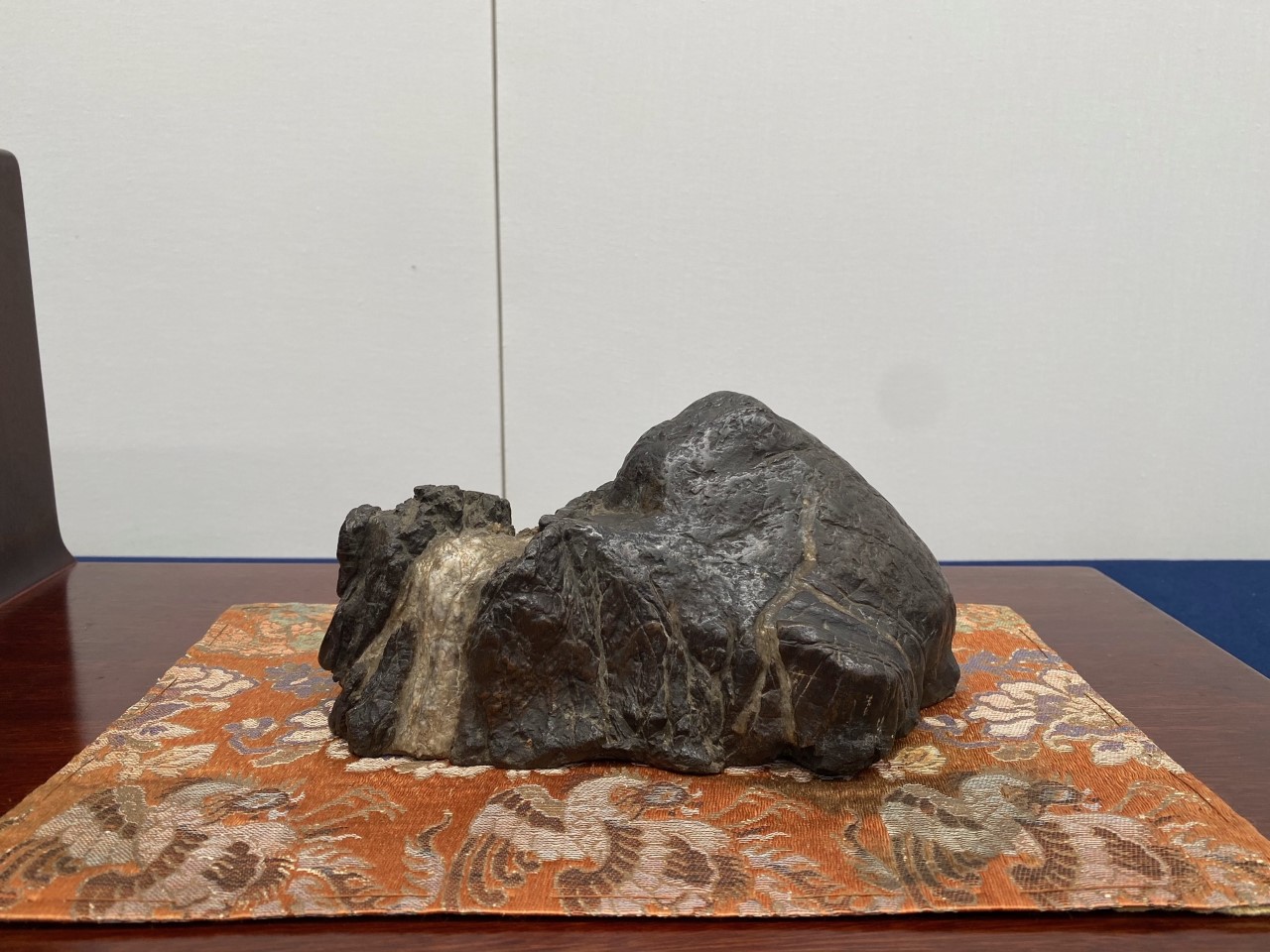

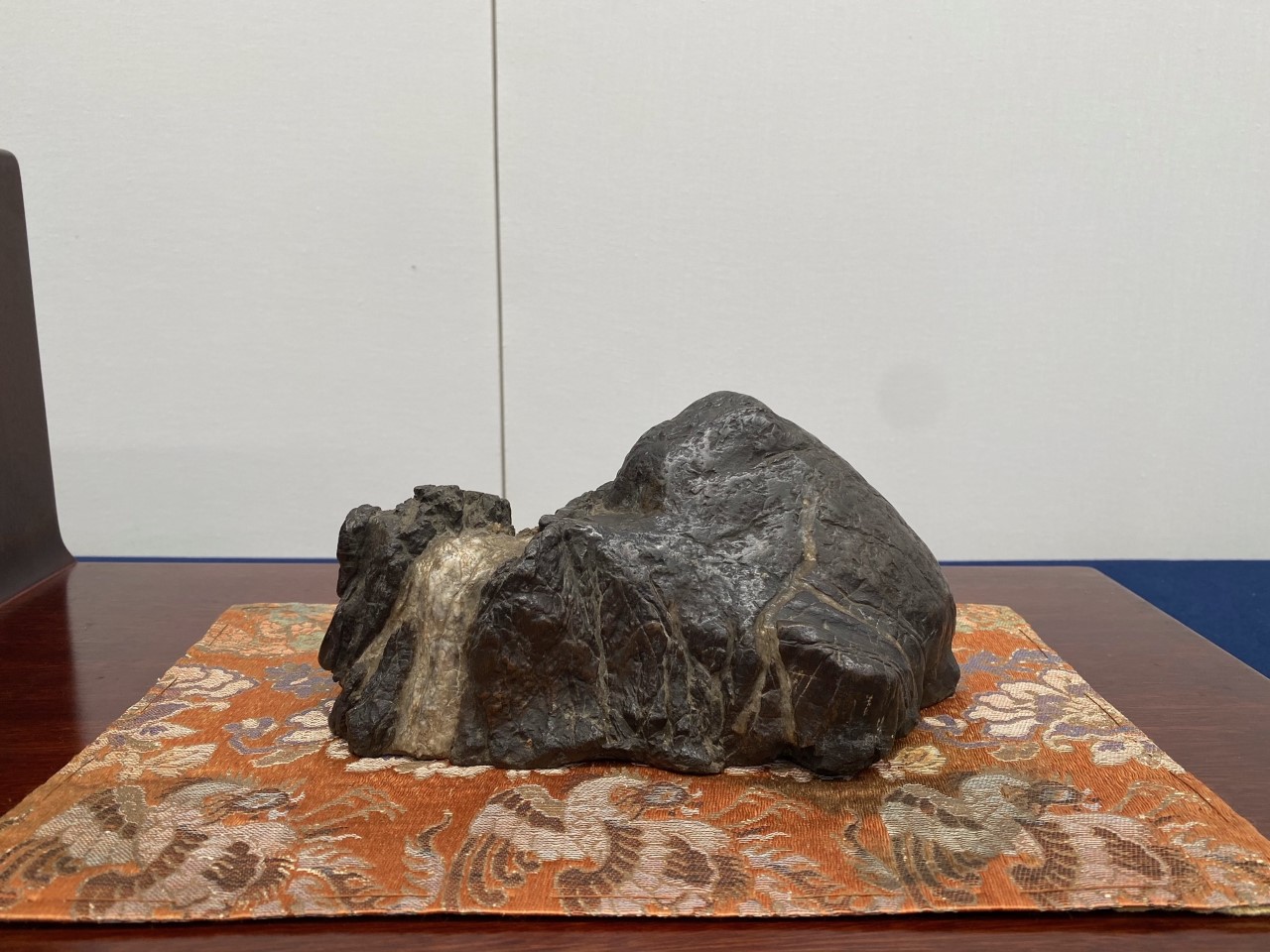

Isogata-ishi - Shore stone (Araiso-ishi Reef stone)

|

Measurement :

|

Lenght

|

⇒

|

20 cm

|

|

|

Depth

|

⇒

|

6 cm

|

|

|

High

|

⇒

|

5,5 cm

|

Origin : Japan (Yase sudachi maguro ishi - Yase Jet-Black Sudachi Stone)

Japan Suiseki Exhibition 2019 6th Edition (Tokyo)

Formerly owned by the great collector Yokoyama Iwao "Uraku" (1923-), with written authentication of Seiji Morimae, Secretary General and CEO of the Nippon Suiseki Association.

1st BSAPI International Suiseki on line Competition 2020

|

|

Our friend Mr. Carlo Vanni, guest of these pages for many years, had the recognition of the Gold Award in the first online competition for Suiseki organized by BSAPi The Bonsai and Suiseki Alliance of the Phillipines, Inc.

With almost three thousand participants all over the world ... sorry if it is little! Our compliments to Carlo's perseverance in proposing his stones, and in firmly believing in them.

|

| |

|

|

| Mrs. Daniela Schifano also had a prestigious award, the Bronze Award, with Japanese stone Haruyama published in her gallery. |

|

|

|

|

Sugata-ishi - Human shaped stone

| Measurement : |

Width

|

⇒

|

7 cm

|

|

|

Depth

|

⇒

|

7 cm

|

|

|

Hight

|

⇒

|

19,5 cm

|

Origin : Japan (Seta river)

2020 U.B.I. Photographic Contest : First prize for Suiseki

Collection by Yokoyama ( 横山 ) "Uraku" Iwao (1923- )

|

Despite the pandemic

The 8th Japan Suiseki Exhibition

by Wil in Japan

Mr.Wil, author of this article, is one of the Directors of the NSA (Nippon Suiseki Association), and gives Italian readers a brief report about the eighth edition of the JSE, the most important suiseki exhibition in the world, in terms of quality and quantity of the suiseki on display, carefully selected. It was a particular edition, which due to the Covid pandemic was nevertheless held even with the awareness of a limited audience presence. In fact, international enthusiasts were unable to go to Japan, and even Japanese enthusiasts avoided going to Tokyo, where "a state of emergency" is in force. We are therefore deeply grateful to him for his comments about some of the stones on display this year which allow us to better understand their history, depth, differences, meanings, paths.

|

|

|

Though the situation was uncertain until only one week before, the 8th Japan Suiseki Exhibition opened as originally scheduled on February 14th, 2021. Soft restrictions applied to restaurants and bars throughout the city, but public museums were allowed to remain open according to their regular schedules. As a precaution, temperatures were taken at the entrance, hand sanitizer was provided, and masks were required at all times while in the exhibition venue, but importantly, the show went on.

|

|

|

As expected, attendance was a fraction of the usual, with no visitors from outside of Japan and very few from outside of the greater Tokyo area for that matter, but there was a great sense of joy and relief in the air amongst those who did attend, as it was likely the first opportunity since last February’s exhibition for many of these old friends to meet and enjoy stones together face to face.

Fearing a poor performance, the Nippon Suiseki Association made extra efforts to encourage participation, and much to our delight, the show had over 170 entries – a new record for the exhibition series, despite the pandemic.

So, with masks on, the tape was cut and the show began (in the picture on the left, the opening ceremony)

|

|

| |

|

The centerpiece of this year’s exhibition was the well-known Kamuikotan stone named “Takachiho” from the Nyogakuan Collection. Its history is elucidated in both the exhibition catalogue and the bilingual Japanese/English publication, Suiseki – An Art Created by Nature – The Nyogakuan Collection of Japanese Viewing Stones (2005).

It is perhaps one of the most revered stones from Hokkaido in the Japanese suiseki world, and one of only a few with a demonstrable prewar history.

|

| |

|

|

|

| "Takachiho" |

| |

|

|

Also in the special entry section was a Sajigawa stone resembling a recumbent bull from the Ukigaya family collection in Chiba Prefecture. As a couple, the Ukigayas have long been patrons of the Nippon Suiseki Association, and though the husband passed away in recent years, Mrs. Ukigaya continues to enthusiastically participate in exhibitions like this still today.

|

|

| From Ukigaya family collection : Sajigawa ishi |

|

| |

|

Near the special entries on an off-set table of its own was the annual display by the Hosokawa bonseki school. Every year since the third installment of this series, the head of the Hosokawa school has been invited as a special guest to create a display and share their art with the suiseki community. This year, using a number of old bonseki that have been passed down within their tradition, they created the scene of a lakeside temple complex, named “The Temple Ishiyamadera off Lake Biwa”. The sensitive placement of each stone and miniature bronze, and the delicate rendering of various designs in fine white sand was indeed a wonder to behold.

|

|

"The Temple Ishiyamadera off Lake Biwa"

Hosokawa Bonseki School |

|

| |

|

Rather than having a separate section displaying important accessories like suiban, doban, and display stands, last year the Nippon Suiseki Association decided to focus an area of the show on stones from a specific place, in that case stones of the Tamagawa that flows by Tokyo. This year too, we intended to organize such an area-specific sub-section of the exhibition, though the uncertainty caused by the pandemic interfered and the idea was put on hold.

In its place, twelve important stones from the privately owned Jizaian Collection were featured. This section featured well-known stones on both daiza and suiban, such as this famous Ibigawa waterfall stone, and a mountain stream Iyo stone beautifully displayed in a lobed suiban.

|

|

| Ibigawa waterfall stone |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Mountain stream Iyo stone |

|

|

Of special interest was also a two-tiered display of historical stones, contrasting traditional Chinese and Japanese display styles. On the upper tier, a well-published antique Chinese stone on a traditional wooden stand named “Mount Emei” after the famous mountain in Sichuan Province; on the lower tier a Kifune bonseki with a wonderful patina displayed on a silk mat named “Nunobiki” after a famous waterfall in Hyogo Prefecture.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| "Mount Emei" |

|

"Nunobiki" |

|

| |

| Though not visible to viewers during the exhibition, the bottom of this bonseki was cut and lacquered, which is a traditional technique commonly employed to protect the lacquered trays used in bonseki displays from being scratched by the rough bottoms of stones. Stones like this are incredibly rare, and highly prized by collectors in the suiseki world today. |

| |

| The tokonoma displays featured the usual variety of seasonal themes, and two displays in particular make for an interesting contrast. |

| |

|

|

|

|

One is an atmospheric nighttime display, featuring a desolate island off in the sea below a moon slightly obscured by clouds, with a single bird in flight above.

Many Senbutsu ishi like this stone have wriggling surface textures and a greyish brown coloration, which in this case matches well with the sea-dragon design and polished bronze coloration of the doban by Harada Houn.

|

|

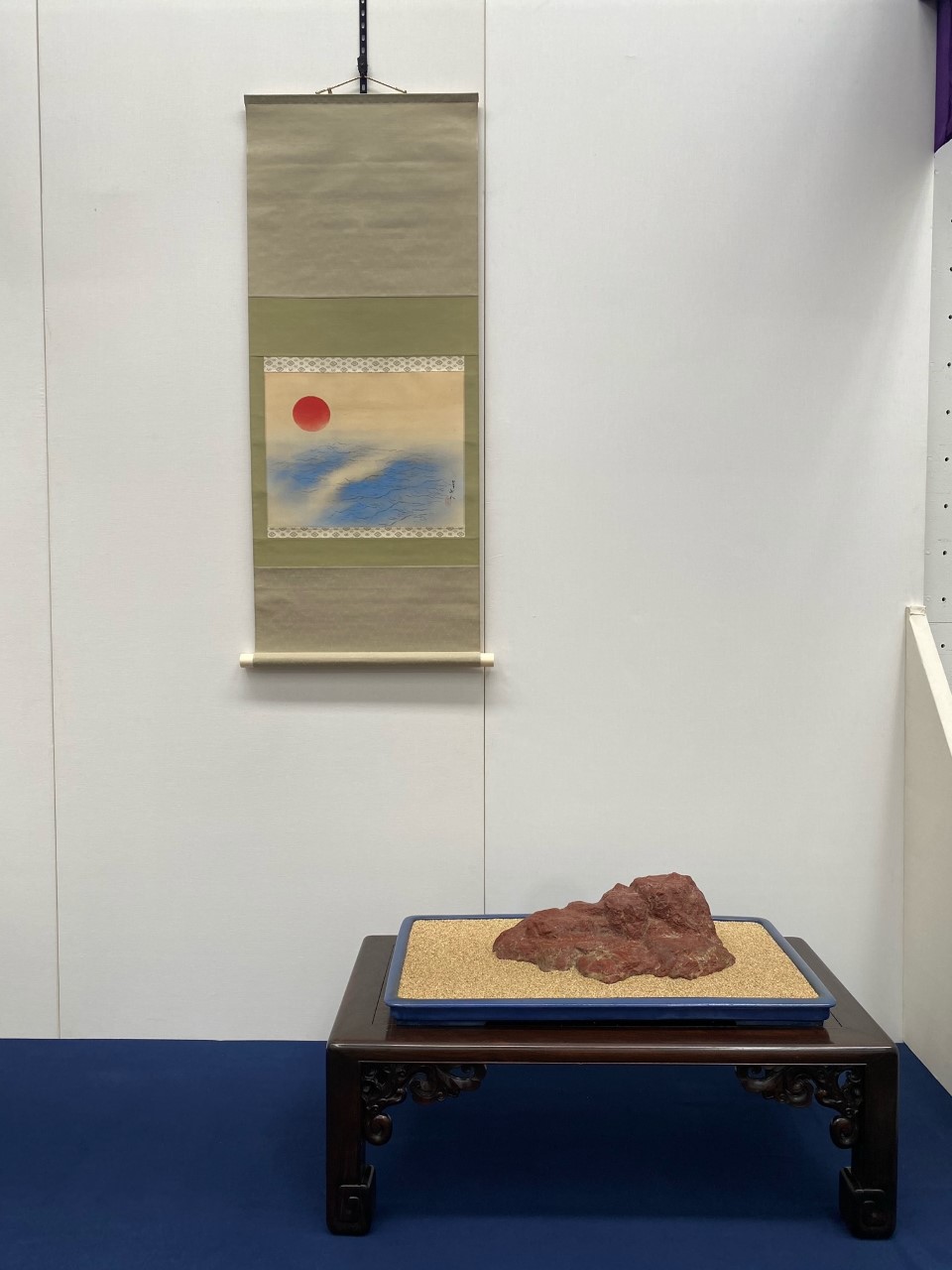

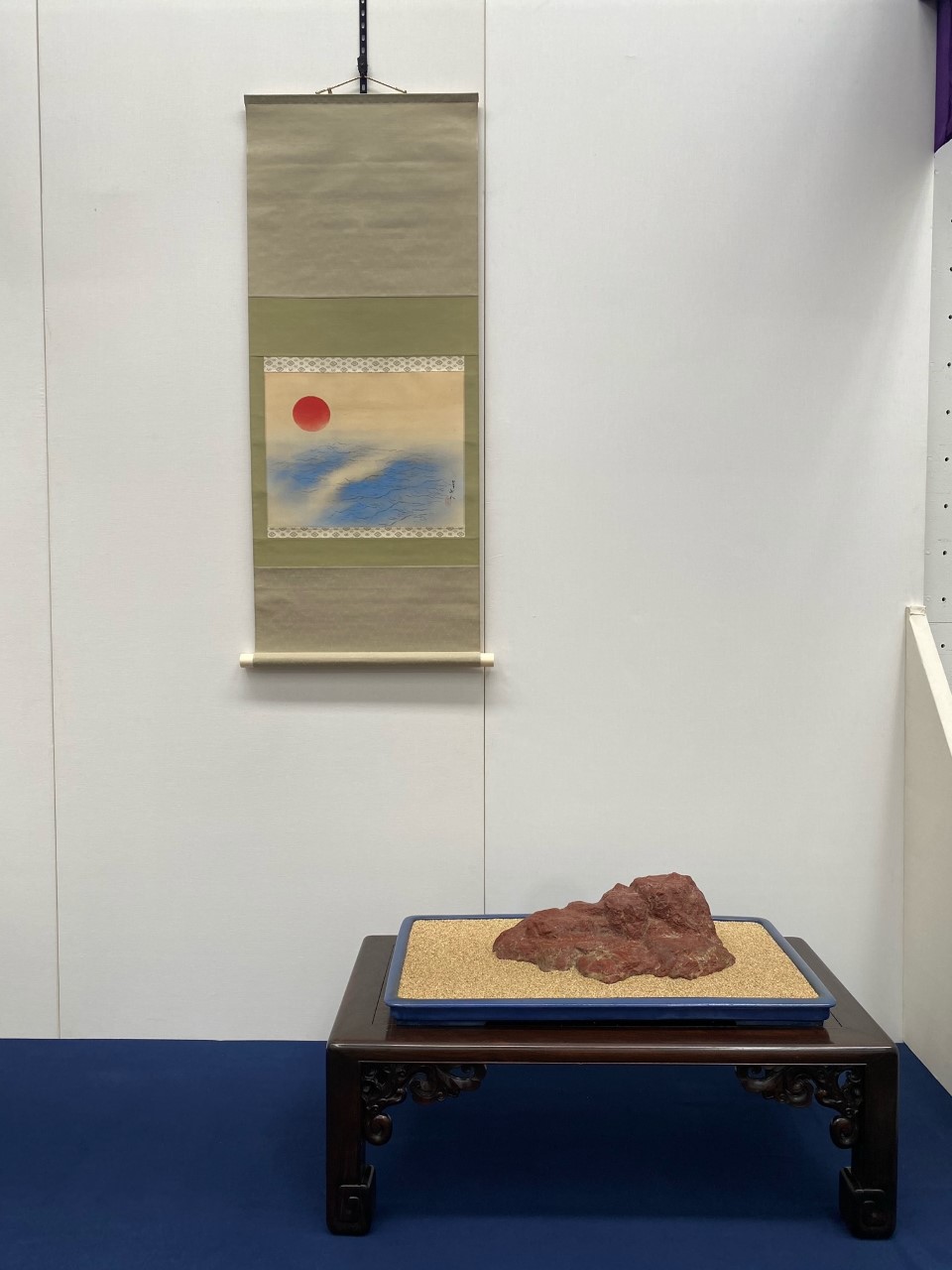

As if its mirror reflection, a colorful daytime display presents a scene of just the opposite intention; an inversion of both form and content. The sun hovers over a clear blue sea, bathing a mountainous island below in bright red light.

The color of the sun in the hanging scroll and the blue pigment used to render the sea perfectly complement the coloration of the Sado akadama ishi and glaze of the refreshingly cool-feeling suiban, making for a perfect match.

The decorative openwork of the stand adds a further sense of flare to the already showy and colorful display, which might be best suited to the New Year, a wedding, or some other auspicious, celebratory occasion.

|

|

|

|

Though doban by this famous craftsman have attracted much attention by Western collectors in recent years, it is important to recognize the characteristics that distinguish authentic works from later reproductions.

The best way to learn this, of course, is to look at and study well-recognized works of the finest quality, which may be difficult without visiting Japan to see exhibitions like this, but quality pictures, they say, can be worth a thousand words. This particular design is one that Houn often employed, and the sharp, detailed lines of the decorative pattern and flawless consistency of the thickness of the rim speak to a quality cast that later attempts by less skilled craftsman never achieved. This is a true masterpiece of its type, and the dark coloration and stern simplicity of the display stand brings a final element of consistency to the brooding atmosphere of the scene. |

|

|

|

| |

| The yin-yang balance observable between these two displays makes for an interesting study on many levels. |

| |

Another important note for discussion observable in this exhibition is the ongoing debate surrounding natural vs. enhanced stones.

As has been widely written about in the past, the Chinese tradition has been far more forthcoming in acknowledging not only that such work is done, but in some cases is even required to improve a stone. Offering a stone a helping hand to bring out the best of its natural features has not been historically objected to in that particular practice, and examples of such stones from China were on display |

|

| Enhanced Chinese stone |

|

| |

|

The Japanese tradition, however, has most certainly not always presented such a clear picture. Different teachings have long existed side-by-side, leaving enthusiasts to choose which practice they prefer, and while for some the issue is black and white, there is no denying a vast grey area in between. Which is not to say that the distinction has been left vague in all cases, but rather that many Japanese collectors appreciate both natural and enhanced stones, and that the views one might hear on the subject vary from person to person in such a dramatic manner that it is impossible to say which is “right” or “wrong”.

|

| Nor should the enhancement of stones be viewed cynically as a phenomenon driven purely by the economic forces of supply and demand in the market of any given time in Japanese history. Long before the so-called “stone boom” of the 1960s and 70s that saw a rapid increase in the popularity of stone appreciation in Japan, stones were being enhanced for a variety of both pragmatic and aesthetic reasons. |

| |

|

Chrysanthemum stones present one area where this phenomenon is quite clearly visible.

The technical aspects and varying extents to which Japanese chrysanthemum stones have been enhanced over the years is most thoroughly discussed in the book, Chrysanthemum Stones: The Story of Stone Flowers by Thomas S. Elias and Hiromi Nakaoji (2010), and examples are almost always to be found in Japanese suiseki exhibitions.

This year was no exception, and two particular entries exemplify different types commonly encountered.

One was a small kawazure, or “river worn” stone in its natural state. Left untouched, it has a fairly dry-feeling surface, and the petals of the flower remain flush with the surrounding material (in the picture on the right).

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

In contrast was an incredibly large stone that could not be moved without the efforts of at least three strong individuals, the flowers of which are so clearly defined and distinct from the surrounding matrix that there is no doubt the natural form of the petals was carved around to make them more explicit and recognizable (in the picture on the left).

Regardless of one’s own preferences, the point is that even at what may be considered Japan’s premier suiseki exhibition, such stones are readily accepted and prominently displayed.

|

|

With over 20 entries from abroad, this year’s exhibition was regarded by all as a great success, despite the ongoing pandemic and limited attendance. As the Nippon Suiseki Association works to finalize the catalogue detailing the entire show, I hope this little review helps inspire discussion and offer encouragement to those of you hoping to organize exhibitions moving forward this year, as we hopefully round the corner of what has been a most trying time for all. |

| |

|

Preserve to transmit

Hoshun'in Bonsai Garden Newly Opened in Kyoto

by Wil in Japan

Wil, author of this article, is one of the Directors of the NSA (Nippon Suiseki Association), and is becoming, with his reports from Japan, an important trait d'union between the lovers of the art of suiseki in the world, in a moment in which we are denied the joy of meeting and sharing. Japan seems at the moment the only country where life seems to continue as always, although with due precautions. I therefore thank Wil for keeping us updated, with pictures and comments, on the initiatives in which he takes part; this, in particular, arises from the intention of transmitting some traditional arts, such as bonsai and suiseki, to the new generations.

|

|

|

|

Though much of life is still on hold due to the pandemic, certain movement is nonetheless taking place. Just last month as the cherry blossoms were peaking, a new bonsai garden opened in Kyoto to a small number of invited guests, which in the future will give interested visitors to the city a new place to put on their list of sites to see.

Mr. Morimae, who has had a long relationship with the temple and organized many exhibitions there over the years, was invited by the abbot to create this space on a plot within the temple grounds that had gone unused for many decades. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

Of course, bonsai and suiseki can be seen in a number of places throughout Japan, but apart from the Taikanten and smaller exhibitions organized by local clubs, there are not many public places in Kyoto where these traditional arts can be readily enjoyed. What makes this new development particularly interesting is its location – the temple Daitokuji. In the northern part of the city, this Rinzai Zen sect temple dates back to the early 14th century, and over the years has been associated with many important historical figures.

Perhaps reaching its peak in the Momoyama and early Edo periods, it remains important to practitioners of the tea ceremony still today, due to its association with Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591), and Kobori Enshū (1579–1647). It is also famed for its multiple rock gardens, and houses old bonseki which have only recently come to light in the suiseki world, such as that featured as the special entry of the 4th Japan Suiseki Exhibition in 2017.

|

| |

|

| The bonseki housed at Shinjuan, part of the Daitokuji temple complex, in Kyoto |

|

| |

|

Being primarily a bonsai garden, that is what takes center stage; and being the cherry blossom season, well… you can guess what was in the first alcove of the indoor display area. A young, weeping cherry tree, with the figure of an elderly man sitting below admiring the blossoms, all under the glow of a full moon.

|

| |

|

|

|

Informed viewers will immediately recognize this as an allusion to the monk and poet Saigyō (1118–1190), who wrote over two hundred poems on the subject of cherry blossoms alone, and one of whose most famous poems is about wanting to die in the spring under the flowering trees. Should we all be so lucky !

|

|

Of greater interest to us, however, are the five suiseki that were on display. An important point to note before considering the stones chosen for the inaugural exhibition, however, is the mission of the garden.

What does it hope to achieve in such a place?

Visitors to the exhibition received a short guide to the displays, with the following statement by Akiyoshi Sokushu, the abbot of the Daitokuji sub-temple Hoshun’in, within whose grounds the garden lays:

"On this occasion, on a plot within the grounds of the Daitokuji complex, we open the first bonsai garden in a Zen temple. Bonsai came from China in the ancient past, and through the varying aesthetic sensibilities of the people who cared for them over the years, they have become the very living form of the Buddha nature that resides in all aspects of the natural world. Fusing bonsai and Zen rock gardens in this historical temple, we created the garden with the hope that a great number of visitors will leisurely look at, discuss, and enjoy the “living Zen and philosophy” that is bonsai.

Suiseki developed over time as well, transforming from the bonseki favored in the Higashiyama culture of the Muromachi period, to the suiseki practice we have inherited today. They are simple stones lying in rivers and mountains, which convey the poetics of landscape beauty. Through the spirit of allusion, they allow people to enjoy boundless worlds in the palms of their hands, or placed in trays.

People, history, culture. Nature, plants, and stones. It is our sincere hope that standing still in this garden, you will all feel something special in your hearts."

|

| With that introduction, it is clear that the purpose is quite simply to introduce these arts to temple visitors who may not otherwise know much about them. Accordingly, the inaugural exhibition was not a parade of great masterpieces put out to impress the cognoscenti, but rather simple, straightforward displays that even someone who had never heard of suiseki could look at and understand. Included were clear examples of the different types you might choose to introduce the art to any beginner: a yamagata ishi, shimagata ishi, taki ishi, and funagata ishi. |

| |

|

Yamagata ishi

|

|

| |

|

| Shimagata ishi |

|

| |

|

| Taki ishi |

|

| |

|

| Funagata ishi |

|

| |

| In another alcove was a three-trunk pine displayed with a small waterfall stone. |

| |

|

|

|

Keido teaches that bonsai and suiseki should not compete with one another in tokonoma displays, and therefore must not be displayed together, but let us remember that bonsai and suiseki were being displayed together in this manner long before Katayama created Keido and its various principles and aesthetic philosophies. In the mid-20th century suiseki experienced great growth in popularity as an independent pursuit, but before that time it was practiced by many as a companion art of bonsai, and displaying them together in this fashion was not at all uncommon in the past.

The important point is that they harmonize. Completely separating them is not the only way to ensure they do not compete.

In this case, the stone is clearly taking on the role of a secondary element in the display, with the bonsai garnering the attention. Figure stones of various shapes, including hut and boat stones, and small landscape stones such as this have long been used as suggestive accessories in bonsai display, and the practice continues in the bonsai world today. The opposite pattern of using bonsai as secondary elements in suiseki display, however, is something one does not encounter in the mainstream.

|

| With the development of this new garden, it is hoped that bonsai and suiseki both will have the opportunity to reach new audiences, helping preserve the traditions in an idyllic setting, while providing a means of outreach to a new generation. |

| |

| |

|

Dedicated to the Deities

"The Covid strikes again"

by Wil in Japan

Wil, author of this article, is one of the Directors of the NSA (Nippon Suiseki Association), and is becoming, with his reports from Japan, an important trait d'union between the lovers of the art of suiseki in the world, in a moment historical in which we are denied the joy of meeting and sharing. Japan has just taken on the challenge of the Olympics and has not held back, allowing athletes from all over the world to put their years of preparation to good use. Some events, of lesser importance, were instead canceled, if kept indoors, to keep attention on the spread of the contagion. Therefore, the Meihinten exhibition was canceled, only the part set up outside the Meiji shrine in Tokyo, dedicated to the souls of Emperor Meiji and his wife the Empress Shoken, took place. Wil photographed and commented for us the 14 suiseki exhibited together with the bonsai. We thank him, with all our heart.

|

|

|

|

|

For the second year in a row, and for only the second time in its history, the Meihinten was canceled once again this year. While the numbers were relatively low compared to many other countries around the world, the Covid-19 infection rate rose dramatically in cities around Japan in April and May 2021, forcing lockdown restrictions to be implemented around the country. When the Meihinten was scheduled to take place in mid June, Tokyo was still in a state of emergency, and being a national institution, the Meiji Shrine decided against hosting the exhibition. Particularly with the summer Olympics scheduled to open only one month later, the push to suppress the infection rate was stronger than ever.

|

| |

|

Normally, the exhibits of the Meihinten are split between two locations: an indoor venue within the shrine complex where the majority of stones are displayed, and an outdoor venue in one of the wings of the main courtyard, where the larger stones are shown alongside bonsai as a way of getting people’s attention and inviting them to explore the main exhibition. It was particularly deemed unsafe to hold a public exhibition indoors, yet the outdoor areas of the shrine were open to visitors, so the shrine decided it was acceptable to hold the annual exhibition of bonsai in the main courtyard, allowing the Nippon Suiseki Association to organize a small show featuring fourteen stones along with the trees.

|

| |

| A message posted by the shrine itself introduced the show to visitors: |

|

|

| Exhibition of Bonsai Dedicated to the Deities |

|

Bonsai trees planted in a small pot can live for several centuries. Bonsai has a history tracing back to the Heian period (794-1185), and the oldest surviving bonsai is said to be the Japanese White Pine cherished by Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604-1651), the third shogun of the Edo shogunate (1603-1867).

A single potted bonsai depicts the grandness of nature and the flow of everlasting time. In recent years, bonsai has also gained widespread popularity globally. This exhibition displays treasured bonsai trees dedicated to the deities of Meiji Jingu

from the Nippon Suiseki Association for your viewing.

|

| Meiji Jingu |

|

| Meiji Jingu : the water ablution pavillion (chōzuya) |

|

|

|

| |

|

As the fate of the show was left undecided until the last minute, it was impossible for the NSA to organize and coordinate an intricately planned installation, so the displays may not have been ideal, and certain entries may look familiar to those who have kept up with the Japan Suiseki Exhibition series.

With time not being on our side, ease and convenience may have been given priority in order to pull the show together, but it was a pleasure to attend nonetheless.

|

| In no particular order: |

|

|

Large Kamuikotan stone from Hokkaido, over 50cm wide, with a fine inlet in the foreground.

Particularly considering the season, this may have been much more appropriately displayed in a suiban, but finding the perfect match for such a large stone can be a challenge even in Japan.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Kotaro ishi from Hokkaido with a deep red coloration.

The airy quality of domon seki like this is particularly refreshing on hot summer days…

surely another good candidate for suiban display.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic akadama mountain stone from Sado Island.

It may break the “rule” that a stone must be easily lift-able by one person in order to be considered suiseki

(at 62cm wide, it surely weighs close to 100 lbs),

but there are few people in Japan who stand in the way of such an evocative stone being admired on a daiza in this manner.

|

|

|

|

|

Large Seigaku ishi from Shizuoka Prefecture over 50cm wide,

with deep shun wrinkles covering its entire surface that give the viewer endless details to explore.

|

|

|

|

|

In contrast, the smooth profile of this Setagawa ishi from Shiga Prefecture

with its signature pear-skin texture

gives the impression of a range far off in the distance, as if outlined in the low light of dusk.

|

|

|

|

The twisting lines and rugged protrusions of this Iyo seki,

particularly as displayed in this light blue suiban,

make a perfect allusion to a craggy shoreline shaped by the forces of nature.

|

|

|

|

|

The sinewy texture and extreme nature of its solitary peak make

this Senbutsu ishi seem as if something taken directly from

a literati landscape painting – a world yet undefiled by the follies of mankind.

.

|

|

|

|

|

Though dry at the time of this picture, this old Ibigawa ishi has a wonderful patina reflecting the long years it has been admired as a suiseki, being sprayed with water countless times to evoke the scene of mountainside streams

converging and flowing peacefully over a calm plateau.

|

|

|

|

Heavily polished and perhaps more biseki in nature, this stone from Sado Island

has purple, red, yellow, and green inclusions mottled together across its entire surface. |

|

|

|

Furuya ishi from Wakayama Prefecture most often tend to be charcoal grey or black in color,

but examples with a rich brown coloration like this massive cave stone, some 60cm wide,

can also be seen every now and then. |

|

|

|

This rare Funakogawa itogake ishi has an intricately detailed texture,

and was named Meoto iwa, or “The Wedded Rock”, which is a name shared by the famous rocks tied together with a sacred rope at the Futami okitama shrine in Mie Prefecture. |

|

|

|

Like the Ibigawa ishi above, this Iyo seki too has a deep patina that could only have developed after years of being regularly sprayed with water, and admired in suiban displays such as this.

The red inclusion on the end and the lighter parts that have eroded away in the midsection

add to the visual interest of this quiet stone. |

|

|

|

|

Easily one of the largest Kamuikotan stones ever seen in Tokyo (60+ cm wide),

this was an impressive stone to behold.

As a mukae ishi, or “greeting stone”, one might expect to encounter such a massive piece at the entrance to a museum or other such public exhibition venue, welcoming visitors to the show.

|

|

|

|

|

This upright figure stone from the Tamagawa was skillfully paired with a red-lacquered display stand of a type inspired by offering tables used in the Kasuga Taisha shrine in Nara. The light inclusion on the right and dark inclusion on the same register to the left balance one another in a thought-provoking manner.

|

|

|

|

Author's note.

|

|

This was an exhibition of bonsai organized by the NSA, which also featured suiseki. In Japanese the name of the show is Hono bonsai ten, which, just as the shrine's translation indicates, means "Exhibition of Bonsai Dedicated to the Deities" [of the Meiji Shrine]. The NSA has organized this exhibition in conjunction with the Meihinten for many years now (remember, many of the NSA board members are also bonsai professionals), but contrary to certain information found online, this was NOT the Meihinten.

|

|

|

Again... Despite the pandemic

The 9th Japan Suiseki Exhibition

by Wil in Japan

Mr.Wil, author of this article, is one of the Directors of the NSA (Nippon Suiseki Association), and gives Italian readers a brief report about the ninth edition of the JSE, the most important suiseki exhibition in the world, in terms of quality and quantity of the suiseki on display, carefully selected. For the second time, due to Covid and the restrictions to contain the pandemic, foreign participants were unable to travel to Japan and the exhibition itself was in doubt, but it nevertheless took place, albeit with limited participation from Japan. This report is therefore even more important, being the only one that comes to us to describe, with full knowledge of the facts, some of the stones on display, selected perhaps for an exhibition that deviates from the canons we know. We are therefore deeply grateful to Wil, for helping us understand, with his explanations, what the stones do not always say.

|

|

|

And so the fun just never seems to end.

The Omicron wave was somewhat delayed in its wash over Japan, but come it did nonetheless, and just as planning for the Kokufu and suiseki exhibition was getting underway. Soft lockdown restrictions went back into place, borders were tightly sealed, and how museums would react remained unclear.

Plans had to be put on hold… again.

|

|

|

While certain exhibitions were indeed canceled and many museums shifted to advanced-reservation, appointment-only admission policies, the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum kept its doors open to both the suiseki association, and the public at large.

The uncertainty meant that publication of the catalogue was delayed, but in the end the show went on.

Having said that, the atmosphere of the exhibition was subdued, to say the least.

While participation from abroad was consistent with years past, no visitors from outside of Japan were able to attend, and in fact very few from outside of Tokyo deigned venture into the big city either, lest they risk bringing the virus back to their local communities – a fair consideration.

Attendance was accordingly low, but one hopes that those who visited did not leave disappointed.

(in the picture on the left, the opening ceremony)

|

|

| |

|

The star of the show was an antique bonseki, never before seen in the suiseki world. It belongs to the Kohoan temple in Kyoto, which is a sub-temple of the Zen sect Daitokuji complex.

Though the exact date is unclear, it has reportedly been housed there, unmolested and in its current manner, since the late 18th or early 19th century, after Matsudaira Fumaiko (1751–1818) displayed it in one of the temple’s tokonoma during a tea ceremony.

|

| |

|

Its manner of display is not one we see in modern bonseki, though books on the subject from the Edo period illustrate the practice and multiple variations thereof.

The stone is cut perfectly flat, and lacquered on the bottom so as not to scratch the delicate surface of the lacquer tray it is displayed in. Placed directly in the center, a perimeter of small white pebbles was then laid out around it in the so-called Moriyama technique.

The effect is one of visual isolation.

Placed in the black tray on its own, the color of the dark stone would blend in and its form would perhaps be partially lost, but the contrasting white field created by the pebbles around it brings the stone into focus, and draws our eyes directly to it. One should not interpret this in a literal fashion – it is not a mountaintop penetrating through a blanket of clouds – but a suggestion of purity, isolating and elevating the stone to a contemplative, conceptual plane.

One would expect nothing less from a bonseki housed in such an important Zen temple.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

In stark contrast was the modern Hosokawa school bonseki display nearby. There is little room for lofty interpretation here. Entitled “Mount Ontake”, meticulous brush and featherwork give life to the image of vast mountain range under a full moon in fine white sand, while in the foreground a group of colorful chrysanthemum stones adds a near-view, seasonal flourish. As sensitive and beautiful as it is, its concrete expression is remarkably different from that of the Kohoan bonseki.

|

|

|

"Mount Ontake"

Hosokawa school bonseki

|

|

| |

|

While we are on the subject, readers of Japan Suiseki Exhibition catalogues will most likely have come across the word “bonsan” and wondered what on earth it meant.

How is it different from “bonseki”? Or “suiseki” for that matter?

While this is not the place to launch into an in-depth analysis of the words’ historical usage, it can be said with certainty that for a time they were used interchangeably and meant the same thing. Specifically, “bonseki” means “tray stone” (盆石), and “bonsan” means “tray mountain” (盆山). And as the majority of bonseki were indeed mountain shaped, and for a time in history the two things were essentially one in the same.

However, in the modern world of bonseki we also do occasionally see non-mountain stones, as witnessed in the previous Hosokawa school display that used pattern stones to give viewers a close up view of a field of flowers, offsetting the landscape in the distance. We also see in bonseki that multiple stones can be used together in one display, and therein lays the difference. The current definition and usage of the word “bonseki” is broad, and while it can refer to a single mountain-shaped stone displayed on its own, it can also include groupings of multiple stones that are not shaped like mountains.

In contrast, in modern times “bonsan” only refers to mountain-shaped stones that are displayed on their own. Most often, they are single peaked, and asymmetrically balanced, though of course those are not definitional requirements so much as they are prevalent tendencies. In truth, the word “bonsan” is not used very often in this day and age, and if you looked hard enough you could most certainly find historical exceptions to the explanation offered above, but this is how people in the NSA use it today.

|

| Back to the exhibition, this year featured a variety of material, including a few fairly unconventional displays that one does not often see in public exhibitions like this. |

|

One was a tokonoma display of a Setagawa ishi in a suiban. If it raised the eyebrows of some, it may have opened the eyes of others.

|

|

|

|

| Setagawa ishi |

|

|

|

Rather than the finely glazed and carefully shaped suiban we are used to seeing, this is a thick, wavy slab of Shigaraki stoneware, made by contemporary ceramicist Tsujimura Shiro.

Sand is spread in a naturalistic manner in the center, and the stone, with its suggestion of a shallow lake on the top, is placed slightly off to the right.

Is it a boat stone?

Or a landscape stone?

The arguably too small ink painting of the moon overhead is in fact by the same artist, and could guide the viewer’s interpretation in either direction. Yesteryear’s orthodoxy may pass such an expression by without giving it due consideration, but those with more of an imagination would surely have found it inspiring.

|

|

|

|

| |

| While thinking in this more creative vein, let us consider two other unique displays. One was a charming little Tamagawa ishi, named “Tale of the Toad” in reference to an old Japanese story. |

| |

| |

|

|

Hats off to the individual who saw the toad when they picked up the stone in the river, and kudos to the daiza carver who completed the picture.

The kumihimo cord knotted in the shape of a turtle adds a bit of auspicious aquatic symbolism, and the decorative mat provides a framework.

Suiseki does not have to be a brooding philosophical quest or high-minded poetic allusion ALL of the time, sometimes it can just be fun.

The literary reference suggested here makes one want to read the story and learn more.

|

Tamagawa ishi

“Tale of the Toad” |

|

|

|

| |

|

A small Kamogawa waterpool stone also demonstrated that there is more than one way of doing things. (picture 7) The stone is named “Chinza fuketsu”, which is difficult to translate concisely, but means something along the lines of “enshrined cave from which cold wind blows”, suggesting a deep opening in the earth with untold mysteries in its depths.

|

| |

|

The “enshrined” aspect of the name pulls it toward the Japanese Shinto tradition, and implies that the cave is sacred, and should be approached with reverence. The arrangement of small grey pebbles around the stone elevates its status by defining a sacred perimeter around it, creating a boundary between our world and the world of the kami that reside within.

Unconventional though such an arrangement may seem, we must keep in mind that there could be a deeper meaning below the surface.

Having said that, from a more practical standpoint it could also be said that while the stone is in fact too small for the suiban, the pebbles enlarge the area it consumes, helping it to balance the space.

One might even argue that the technique has an historical precedent of sorts, as witnessed in the Kohoan bonseki display previously discussed. Here, it accomplishes two things, one conceptual, one visual.

Two birds, one stone (and a handful of pebbles).

|

|

|

| |

|

Kamogawa waterpool stone

“Chinza fuketsu” |

|

| |

|

Of course, the vast majority of displays were more in line with what you would expect to find in a Japanese suiseki exhibition.

This Kanayama ishi from Hokkaido was simply named “Cape”, and presents us with a dramatic seaside promontory. Careful inspection reveals a tunnel passing through its center, and the fan-shaped painting of geese descending against a full moon identifies the season as autumn. One can almost feel the cool breeze blowing over the ocean.

|

|

|

|

Kanayama ishi from Hokkaido

"Cape" |

|

| |

|

Another autumn scene presents a very different picture. This well-known stone has been mistakenly published as an Ibigawa ishi in the past, when in fact it is a beni Kamogawa ishi, with an auburn coloration so deep it is almost unrecognizable. The stone’s soft, dull patina is incredibly old, and suits the subdued tenor of the season established by the painting. Use of the bright white suiban is certainly debatable, but surely the exhibitor had their reasons.

|

|

|

|

|

| beni Kamogawa ishi |

|

|

|

|

|

The special exhibition area this year focused on the collection of one Honde Kozaemon, who owns a number of important suiseki, including this wonderful Setagawa kin’nashiji ishi.

This type of Setagawa stone is quite rare, and its beauty speaks for itself.

|

| Setagawa kin’nashiji ishi |

|

|

|

|

|

This well-known Mikura ishi from Shizuoka Prefecture shows beautifully on its thin daiza, and is one of the most recognized waterpool stones in Japan. Its center is deeply eroded, and resembling a tsukubai (type of stone washbasin found in Japanese gardens), it is the type of stone that would appeal to practitioners of the tea ceremony.

|

|

|

|

|

| Mikura ishi |

|

| |

|

|

Ubusan seki like this are of a very dry looking, almost sandstone like material, which perfectly suits the atmosphere of a dilapidated hut stone like this.

|

|

|

| |

|

Ubusan seki

Dilapidated hut stone

|

|

|

|

|

|

This doban display of a coastal Kamogawa ishi on a bamboo display stand is perfect for summer.

Seeing it here in the cold month of February makes one anxious for warmer weather to come soon.

|

Coastal Kamogawa ishi |

|

|

|

| |

|

| Despite the attendance and reserved atmosphere of the time, there were a number of inspiring entries this year, and we can only hope that peace prevails throughout the world in the months to come so that the 10th installment of the exhibition next year will be a great success, and a show to remember. |

|